3. CHLOROFORM

Chloroform. CHCl3 .Trichloromethane. A colourless volatile non-flammable liquid with a characteristic smell and a sweetish taste.

Putney, London

‘John, John, come here,’ my father called from downstairs. ‘I’ve something to show you.’

I was in my bedroom, stretched out upon the floor, reading King Solomon’s Mines for the third time since my fourteenth birthday. I got up quickly and ran across the landing to the top of the stairs.

‘Coming, Dad. Coming.’

The stairs were steep but I took them two at a time, landing heavily on the steps and arriving at the bottom in a flurry of arms and legs. I crossed the hall and entered the surgery. There was the usual strong smell of oil of cloves mingling with the softer scent of the pink bubbling mouthwash. The room was bathed in bright sunlight and the dental chair looked surprisingly cosy and inviting. My father was standing by the fireplace looking intently at a drinking glass that was upside down upon the mantelpiece.

‘Look at this, John. I’ve got the most beautiful bumble bee here. I thought it would be fun to give it some chloroform. Don’t worry, we won’t hurt it. We’ll let it wake up again and set it free.’

‘How will we give it some chloroform?’

‘We’ll put some on a piece of cottonwool and just pop it under the edge of the glass.’

He walked over to a glass-fronted cabinet in the corner of the room. From the top shelf he took a small dark green six-sided ridged glass bottle[1]. It had a clear glass stopper at the top that he removed. Picking up a small piece of cottonwool he put it over the mouth of the bottle and tipped it upside down for a moment. He carefully replaced the stopper and put the bottle back into the cabinet.

‘Now we’ll just lift up the edge of the glass, and there you are,’ he said as he slipped the wet cottonwool under the rim and let the glass down again. The bee, plump, beautiful and angry, buzzed noisily, vainly trying to fly through the side of the glass. For a moment or two nothing happened, and then the bee started to falter in its flight, suddenly dropping an inch or two, then struggling to regain its original height. Each time it fell the sound of its buzz became lower in pitch and unsteady as well. After another minute or so it settled onto the ground and started walking around the small area of mantelpiece bounded by the rim of the glass, occasionally trying to take off but failing to do so. Eventually it stood quite still and silent. My father lifted the glass up and touched the bee with his finger. It stayed quite motionless.

‘Is it dead?’ I asked fearfully.

‘No, certainly not. It will soon wake up. Just be patient.’

It was nearly five minutes before it moved, and then at first it staggered around like a drunkard, making us laugh out loud. Finally it seemed to pull itself together, and with a furious buzzing it launched itself off the mantelpiece and meandered across the room towards the window. I followed it and opening the window wide I guided the bee out into the warm sunny garden.

‘That was amazing, Dad. Have you ever done that before?’

‘Not since I was learning physiology and pharmacology at dental school, and that was many years ago. Nobody uses chloroform these days because it poisons the liver and is bad for the heart, but it was very useful in the old days.’

The doorbell rang.

‘That will be my next patient. See you at lunch, John.’

‘OK, Dad. Thanks for showing me the bee and the chloroform. It was really interesting.’

Back upstairs I was still excited by what I had seen. I went to the bookcase in the drawing room, took the dictionary from the bookshelf and looked up chloroform:

a limpid, mobile, colourless, volatile liquid (CHCl3) with a characteristic odour and a strong sweetish taste, used to induce insensibility.

I didn’t know what limpid meant, but it sounded a lovely word. Mobile seemed unnecessary (surely all liquids were mobile), but I knew all about that characteristic odour. I remembered meeting it for the first time when I had had terrible diarrhoea just after Xmas. My mother had given me a thick pale brown medicine, which she had shaken vigorously before pouring it out of the bottle. It had tasted both foul and fascinating at the same time, and it had smelt just like the chloroform we had just been using downstairs. Dad had said at the time that it contained chloroform water, whatever that was[2].

I wondered if there were any more books around the house in which I could read about chloroform. I knew that my father had some textbooks on the shelves in the waiting room so I went downstairs again and searched amongst them. To my delight I found a very important looking book all about anaesthetics[3]. The date inside said 1940, so I was only six when it was published. It was mostly not about chloroform, but about things like cylinders and gases, and rubber bags from which people could breathe.

There were also some coloured pictures showing what happened if patients did not get enough oxygen - they went purple in the face, just as you would if you were strangled, and pictures of machines like the one in my father’s surgery which had four cylinders, some glass-covered dials, plenty of shiny metal and two black tubes running to a small mask that fitted over the patient’s nose. It was very interesting.

I turned to the short chapter headed CHLOROFORM and read it carefully:

... Colourless liquid with a sweet, burning taste...

Yes, that’s how the diarrhoea medicine had tasted, sweet and burning.

... and an agreeable smell.

Well, I wasn’t so sure about that.

It is sufficiently irritating to cause a mild burn if the lint on which it is dropped is kept in contact with the skin for some time.

Lint? That was a lovely word, wasn’t it? I had always liked the sound of lint ever since I was a small boy and mother had used it to cover the poultices she put on the boils I had during the war. Why was it, I wondered, that some words were so comfortable and reassuring? Lint was certainly one of them.

The specific gravity of the liquid is 1.5 and its boiling point 61oC.

I thought that probably meant chloroform was heavier than water, and that it boiled easily, but I wasn’t sure.

Chloroform vapour has a density of 4 and shares with nitrous oxide the great advantage of noninflammability.

The vapour was much heavier than air and it wouldn’t burn.

Chloroform is highly toxic, anaesthesia being achieved by a poisoning of tissue cells appreciably greater than that produced by other anaesthetics.

That didn’t sound very nice!

An even more serious deterrent to its use, however, is that during induction sudden death, which is unpredictable and apparently unavoidable, occasionally occurs.

That sounded even worse!

It has the advantage over ether that its vapour is quite pleasant to inhale, and on that account it was formerly in common use to produce unconsciousness before continuing anaesthesia with ether. That justification for its use has been eliminated since the introduction of basal anaesthetics. Its employment in general surgery is now rare, and its use in dentistry unwarranted. Its physical properties give chloroform a sphere of usefulness for emergency operations conducted away from hospital.

The next section was all about the dangers of chloroform. It could do terrible things to your heart, it could stop you breathing, and it could give you delayed poisoning:

... in which condition liver function becomes grossly disorganised. This grave complication, the signs of which do not occur for some thirty-six hours after administration, is more likely to occur in exhausted patients, in those depleted of tissue fluids, and in those who have been deprived of food. The risk of this complication increases in proportion to the degree of debility of the patient and to the amount of chloroform given.

I certainly could understand now why my father had said they did not use it much today. Despite this the book went on to tell you how to give chloroform to people.

Chloroform may be administered from a drop bottle on to a Schimmelbusch’s mask

What on earth was a Schimmelbusch’s mask? Anyway it had a splendid name, whatever it was[4].

...Covered with eight layers of gauze or one layer of flannel. A few drops are placed on the flannel and the mask gradually lowered on to the face. The rate of administration is increased as rapidly as the patient will tolerate. Swallowing, breathholding, or coughing are signs that the concentration is being increased too quickly. If they occur, the mask must be withdrawn a few inches, and gradually lowered as normal respiration is resumed.

On the next page there was a drawing of what looked like a hanky whose corner had been pulled partly through the middle of a closed safety pin. Underneath was written:

In order to avoid too strong a concentration of chloroform vapour, Lister in 1882 recommended that the mask should consist of the corner of a thin hand towel drawn through a closed safetypin. The towel should not touch the face. And although if necessary it may be kept moist with chloroform, the amount on it should never be sufficient to cause the chloroform to drop off the edges.

Here the chapter finished. Clearly chloroform was a thing of the past, though certainly it had been important once. Perhaps the first chapter of the book, which was called The History of Anaesthesia, would tell me more. It was page seven before chloroform was mentioned. Here it said:

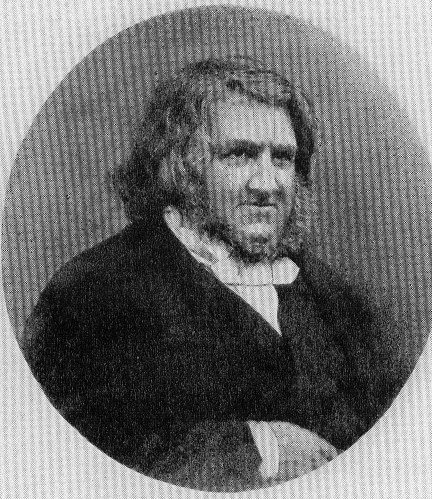

Simpson (1811-1870)[5] was the first to use chloroform as an anaesthetic. In a paper to the MedicoChirurgical Society of Edinburgh on 10th November, 1847, he wrote, ‘I am enabled to speak most confidently of its superior anaesthetic properties, having now tried it upon upwards of thirty individuals’. His success with chloroform, coupled with his enthusiastic championship of it, quickly convinced the medical profession, not only in Great Britain but also on the Continent, and to a certain extent even in America, that chloroform was indeed far superior in every way to ether. This widespread belief produced both evil and good: evil, because chloroform is intrinsically dangerous; good, because the recognition of those inherent dangers was more powerful than any other factor in promoting scientific investigation into the nature of anaesthesia and of anaesthetic agents.

James Young Simpson

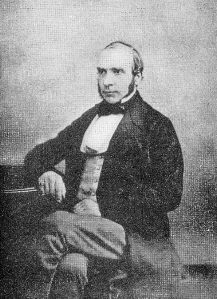

The chapter went on about a Yorkshire doctor called John Snow who wrote two books about anaesthetics[6] and who then

... set the seal of propriety on anaesthesia in obstetrics, when in 1853 he administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of Prince Leopold, and again in 1857 at the birth of Princess Beatrice.

I was fascinated. I knew that having a baby was painful but I didn’t really understand all the details. Still it seemed a good idea to take the pain away if you could. It was lucky that Queen Victoria’s heart had not stopped suddenly and unpredictably like the book had said could happen. That would have been terrible. Perhaps they would have executed Dr. Snow for treason! I realized that that was rather unlikely, but he might have been put in prison, or deported or something.

John Snow

I flipped the pages over. Chapter 4 was all about why and how you breathe.

The lungs are divided and subdivided many times... It is estimated that owing to these divisions, the surface or ‘breathing’ area of the lungs is 200 square metres or 110 times that of the skin covering the body.

Amazing! I wondered why didn’t they teach you things like that at school. Perhaps they didn’t know about it themselves, or surely they would tell you.

I looked at my watch. It was nearly one o’clock. Time for lunch. I felt really hungry, so I shut the book and made my way to the kitchen to see if lunch was nearly ready.

‘Hi, Mum. How long till lunch?’

‘It won’t be long, dear. Just put the salt and pepper on the table, there’s a good lad. Dad will be up in a moment.’

Lunch turned out to be one of my favourites: smoked haddock with a poached egg on top. Delicious! I loved the big thick flakes of fish, especially when they were dipped in warm runny yolk.

The conversation during lunch was mainly about the Daily Telegraph crossword, which was the normal routine at midday.

‘1 down: P something E, three letters T, four letters N. Best in prayer? Sounds like an anagram..... Got it! Presbyterian. That’s a good clue, isn’t it?’

I had to agree. It really was very clever. I had made up a crossword or two in my time, but I had never managed to concoct a clue as satisfying as that one. Still they were doing it every day, so they ought to be better.

‘12 across: C six letters. Foods apparently not eaten at one sitting.’

There was silence for a few moments. I wondered what on earth that could be. Suddenly it came to me.

‘Cereals! I think it must be cereals.’

‘Well done, John,’ said father. ‘That’s a good clue too, isn’t?’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘John,’ said my mother, ‘would you do something for me? I forgot to take my purse with me when I went to the fish shop today, but Tom said not to worry and to pay him next time I was passing. I really would appreciate it if you would take him the money this afternoon. I feel rather silly about it.’

‘O.K., Mum.’

‘Thank you, dear.’

Half an hour later I was on my way across the railway bridge and down the alley beside the pub. Soon I was at the fish shop and the debt was settled.

‘Come and see the eel that I’ve got here,’ said Tom.

I walked to the back of the shop and looked into the sink where Tom was pointing. In it was a live eel, swimming around looking sleek and beautiful.

‘Would you like to have it for a pet?’ said Tom. ‘I’ll give you a bucket to take it home in, if you like.’

I looked at the eel with a mixture of apprehension and delight. How I wanted to say ‘yes, please!’ and yet how could I? My mother would be horrified, and probably my father too. But what a lovely creature!

‘Oh, yes, please. I’d love to have it to take home. I’d look after it ever so well. Really I would.’

A few minutes later I was on my way back home, the bucket swinging by my side, my step jaunty and my mood exhilarated. What a nice man was Tom.

‘I’ll bet not all fishmongers are like Tom!’ I called out loud to the world at large. ‘I’ll bet they’re not!’

A little old lady walking quietly along Quill Lane looked up in surprise. I smiled at her.

When I got home I walked round the back of the house but stopped when I reached the summerhouse. I could see my mother through the kitchen window. I waited until she had her back turned and then slipped past so that she would not see me reach the back door. A few moments later I was up the stairs and the eel was in the sink in the dental workshop.

The dental workshop was a marvellous place for a youngster to play in. I remembered how before the war, when I was only five, I was not allowed into the room at all. Even when we came back to live in London in 1943, when I was nine, I was not allowed in the workshop unless the one of the dental mechanics was there to keep an eye on me. With their encouragement I soon learnt how to make a model of my teeth in plaster of Paris, first softening the impression material in hot water, then pressing it into the metal tray before popping it into my mouth and biting on it. It tasted decidedly unpleasant but a little determination soon allowed you to get used to it.

It was important to keep your teeth quite still while the composition cooled, but this only took a couple of minutes and then with great relief you could gently ease the whole thing out of your mouth.

Next there was the plaster to mix and to pour into the mould, which you had to tap and shake from side to side so that the bubbles inside rose to the top. As the plaster started to set so you must pile more on top so that it had a base on which to stand, which itself had to be shaped and smoothed. What excitement there was at the moment you took the model out of the mould. Would there be bubbles spoiling the edges of the teeth? If there were you would have to start all over again. If there were not any bubbles then you could glory in the beauty of the fine white plaster and the skill that you had shown in producing it. It really was tremendous fun! At night-time if no one was around you could collect up all the leftover pieces of dental wax, boil them together in a ladle and pour the bubbling liquid out of the window in a steady stream. The workshop was on the third floor, and after falling one storey the wax would burst into flame, and then continue burning all the way down till it hit the ground. It was very dramatic and exciting. Another favourite trick was to make a tube of plaster closed at one end, and when it was set to put it in a vice at an angle pointing towards the ceiling. Then you took the small lead squares out of the used X-ray packets, melted them in a ladle over the Bunsen burner and poured the hot liquid into the plaster tube you had made. Although it seemed dry to the touch there was actually a lot of water left in the plaster, and when the lead reached the bottom of the tube it was still hot enough to turn the water into steam. With a great whoosh the expanding steam would hurl the lead up the tube and out of the top, so that it shot across the room and spattered onto the ceiling with a satisfying thud, solidifying as it did so, sometimes sticking to the ceiling but often dropping to the floor like a silver starfish. Dangerous, brilliant fun!

Now I had my very own eel in the workshop!

It really was an amazing creature. I watched as it swam back and forth, round and round, not stopping for several minutes, now pausing briefly, now starting off once more. After a while it became rather tedious just watching it swim round and round. I started to think about what I could give the eel to eat. Bits of meat, worms from the garden, minnows or tadpoles? Yes, any of those would do. My interest rekindled, I became quite excited by the prospect of searching for the right foods.

I wondered if the eel would get out of the sink if I went downstairs, but it had made no attempt so far to do anything that looked as though it could escape. Still I would cover the sink to be sure. I glanced round the room and saw in the corner a sheet of cardboard which I put across the top of the sink, taking care not to get it wet. Then off down the stairs again.

Out in the garden I started to dig in the flower bed, carefully out of sight of the kitchen window. In no time at all I had eight wriggling worms of various sizes. What a splendid meal these would make for my fine eel! I popped them into a jam jar and slipped up stairs once more.

The eel was still swimming round looking altogether out of place in the small sink. I began to wonder if I had done the right thing, for it did look so cramped and unhappy. Tentatively I dropped the worms in the water, but the eel ignored them completely. Round and round it swam quite unceasing. It was rather eerie. If only it had room to stretch out fully instead of being curled into a tight circle. Eventually I thought that the best thing would be to cover the sink again and leave it alone for a while. Perhaps it would eat the worms if I wasn’t watching so closely.

Ten minutes later I was talking to my mother and wondering whether to mention the eel or not. Better not!

‘Can I look in the fridge and see if there is anything to eat?’

‘Surely you can’t be hungry. It’s only a couple of hours since you had lunch.’

‘I’m starving, Mum. It’s ages before supper. I’ll never last till then. I’ll just look for a small snack. I promise I’ll only have a little something to keep me going,’ and without waiting for an answer I opened the fridge door. A couple of cold sausages immediately caught my attention one for me and one for the eel upstairs.

‘There’s two sausages here. They’ll do fine. Thanks a lot, Mum,’ and I was gone almost before the fridge door had swung shut.

When I got back to the workshop the eel hadn’t touched the worms which by now had stopped wriggling and were lying motionless at the bottom of the sink. I added a few pieces of sausage and tried to feel hopeful about it. I ate the rest of the sausage while I watched, but it was all in vain. True the eel had at last stopped swimming around in its endless circle, but it ignored the pieces of sausage completely. It looked even more hopeless and pathetic now that it was stationary than it had when it had been swimming around. An occasional twitch of its tail showed that it was still alive.

‘Whatever am I to do with it?’ I thought. It had seemed such a good idea to have it at the time. I looked again at the creature. It really was a beautiful thing. But what was I to do with it? I decided to not to worry any more for the moment. I would leave it where it was till tomorrow and then see how I felt about it. I covered the sink with the sheet of cardboard on which I wrote in large letters

DO NOT TOUCH. LIVE EEL. THANK YOU.

Downstairs I waved at my mother as I passed the kitchen.

‘I’m going out on my bike. I’ll be back by supper time.’

‘Be careful on the roads. The traffic is very bad at this time of day.’

‘O.K., Mum,’ and I was gone.

The South Circular Road was busy as ever. Soon I had left the bustle behind me and I found myself down by the river. The water was its usual dirty brown colour with an amazing amount of rubbish floating in it. There were old bottles, tyres, cans, boxes and the other things that always puzzled me as they drifted by, but which I hadn’t liked to ask anyone to explain to me. They looked like elongated balloons and I thought they were the things that were on sale at the hairdressers, but I wasn’t sure. There were an awful lot of them whatever they were[7]. I leant my bike against the wall of the cafe where five years later the police would pick up the mass murderer Christie, and my bike had been there too at the time, just as it was this day. I walked along the road by the side of the river looking ahead into the distance where the water curved past the Fulham Football ground and on towards Mortlake. It was so reassuring in its familiarity that I managed to put the problem of the eel out of my mind altogether. I walked on, past the boathouses, till the road gave way to the footpath along the river bank. Though the sun was shining there was a keen wind and the surface of the water was much choppier here than by the bridge.

I chose a spot on the grass close to the water’s edge. First I lay the bike down, and then myself. The ground was bumpy but I didn’t notice it. I started to think about the eel once more. It had seemed such a good idea at the time. What was I going to do with it? It had looked so unhappy in the sink. Perhaps I should kill it humanely, and then dissect it. That wasn’t a bad idea at all. It would solve the immediate problem and be fascinating at the same time. Yes, that was a good plan. I hesitated for a moment or two longer and then suddenly the decision was made! Yes, that was what I would do. But how to do it? I was quite sure that I wouldn’t be able to kill it with a hammer or an axe or anything like that. Perhaps the chloroform in my father’s surgery would be the answer! Yes, that was certainly it, so I might just as well get on with it. I got up quickly, picked up the bike, jumped on and set off at a furious pace for home.

I managed to get into the house without being seen. I knew the chloroform would be in the surgery and that the surgery would be empty on a Saturday afternoon. It took only a moment to open the cupboard and pick up the bottle. Half a minute later I was in the workshop. The eel was in the sink just as I had left it. Certainly it couldn’t stay in the confined space any longer. I took the stopper out of the bottle and paused for a second. It surely would be the very kindest way to kill the poor creature. Of course it would.!

I lifted the bottle carefully and held it over the basin. Here goes then. I poured some of the chloroform into the water.

I was quite unprepared for the violent reaction from the eel, which instantly began thrashing around in the most terrifying manner. I felt the sweat break out on my forehead and I could feel my heart pounding. Surely the chloroform would work soon. It seemed ages before the eel quietened down, but probably it was only a minute or so. I watched anxiously, hoping that peace would soon come. But a moment later the eel was thrashing around once more. Would it never stop? When finally it did become still I was horrified to see the outer layer of the eel’s skin was peeling off. Oh, God, what had I done? I had only meant to kill it as kindly as possible.

At last it was quite motionless. Surely it would not come round another time. I must make certain it did not.

I puzzled about it for a few moments and then I remembered that I had a syringe in my biology dissecting kit[7]. I would inject the eel with some chloroform! That would do the trick. I quickly fetched the syringe and soon had it filled. I paused for just a moment. I hoped it would not jump when I stuck the needle into it; that would be terrible. Gingerly I advanced the point towards the motionless animal. I sighed with relief when it remained quite still as the needle pricked the skin, and then went on deeper on into the muscle. I pressed the plunger and the job was done. It seemed a shame really. I wished now that I had taken it down to the river and thrown it into the water, but somehow I just hadn’t thought of that, and it was altogether too late now.

Briefly I considered dissecting the lifeless corpse, but I decided not to after all; instead I buried it in the garden.

Denver, Colorado

Nearly twenty years were to pass before I saw chloroform given to a patient in an operating theatre. The anaesthesia was entirely unremarkable. If it had not been for the different smell as Doug poured the chloroform into the beautiful ‘copper kettle’[1], and that he had written trichloromethane on the anaesthetic chart, I would not have been able to distinguish it from halothane anaesthesia (chapter 6).

I have not seen it used since that day, and I am not likely to see it used in the future[2].

Southmead, Bristol

I had thought that this chapter was finished, but then Tom Simpson came to work with us at Southmead. It turned out that he was the great great great grandson of James Young Simpson. The family resemblance was unmistakable. It took me several weeks to arrive at the point where I did not mention his ancestry every time I met him. Finally I managed it. Then two things happened: first, I met Joseph Clover's[1] great great grandson at the History of Anaesthesia meeting at the Royal Society of Medicine, and I told him all about Tom. He himself was in banking, but his son was just about to qualify as a doctor. I wondered whether he too would become an anaesthetist. Then later in the year the Wellcome Foundation sent around an advert about their new relaxant drug Mivacron. On it was the tale about Simpson and his friends getting high on chloroform; Simpson was depicted as lying under the table.

‘It's quite scurrilous,’ I told Tom, who had not seen the advert. ‘You should give a paper at the next meeting of the South West Society called The Truth about my Great Great Great Grandfather. Unless, of course, it is all true.’

‘I think it may have been. He was a pretty wild character, you know.’

‘Yes, but a remarkable one all the same. Have you read the chapter on him in Victor Robinson's splendid book Victory Over Pain[2]. I'll lend it to you if you like, but do let me have it back; it's my favourite book - well, after The Oxford Book Of Quotations and the Collected Works of Oscar Wilde, of course.’

That evening I took Victory Over Pain off the shelf and read again how on November 4th 1847 Simpson and his friends first breathed chloroform, and how

One of the young ladies, Miss Petrie, wishing to prove that she was as brave as a man, inhaled the chloroform, folded her arms across her breast, and fell asleep chirping ‘I'm an angel! Oh, I'm an angel!’

As it happened Miss Petrie was not the first female to fall unconscious from breathing chloroform. In the previous chapter Robinson had told how around 1830/1 the 8 year old daughter of Samuel Guthrie, who discovered chloroform, would often put her finger into the liquid and taste it, and how one day its heavy vapour put her off to sleep. I wondered if she, too, thought she was an angel!

NOTES

[1] Chloroform when exposed to air and light gradually undergoes oxidation, which results in contamination with phosgene and chlorine. This oxidation is retarded if 1-2% alcohol is added and a dark bottle is used.

[2] ‘Chloroform water’ is defined as 0.25% (v/v) chloroform in freshly boiled and cooled water, but it is often used at double strength as a preservative, a carminative and a flavouring. Mist. Kaolin et Morph., a once popular treatment for diarrhoea, which can still be found in the British National Formulary (though sadly no longer in the Latin) has Tincture of Chloroform added to it rather than chloroform water. The safety of the long term use of chloroform in mixtures has been questioned and in any case its action as a preservative is short-lived once the mixture is exposed to the air.

[3] Macintosh R.R. and Pratt F.B. Essentials of General Anaesthesia. Oxford:Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd., 1940. See also chapters 2 and 3.

[4] Use of the Schimmelbusch mask is described in chapter 2, 1955.

[5] Sir James Young Simpson (1811-1870). Professor of Midwifery, Edinburgh University.

[6] John Snow (1813-1858), was the leading anaesthetist in London until his death in 1858. In 1844 he had been a lecturer in forensic medicine at Aldersgate, but he was appointed Anaesthetist to St. George’s Hospital in 1847, and then to the staff of University College Hospital, where he worked Robert Liston, and King’s College Hospital. His two books on anaesthesia were: On the Inhalation of the Vapour of Ether in Surgical Operations in 1847, and On Chloroform and Other Anaesthetics in 1858, both published by Churchill of London. Snow is famous also for having the handle of the Broad Street water pump removed on September 8th 1854, thereby preventing a recurrence of an epidemic of cholera. For further information on this remarkable man do visit http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow.html and http://www.epi.msu.edu/johnsnow/index.htm or read Vinten-Johansen et al on Cholera, Chloroform and the Science of Medicine, A Life of John Snow. OUP 2003. - an excellent book. There is also a John Snow Society, see http://www.johnsnowsociety.org/, whose only requirement for membership is that you visit The John Snow Pub, Broadwick Street, Soho, which is on the site of the original pump.

[7] It is amazing to think how society and its attitudes have changed; at fourteen I had never heard the word ‘condom’, and at fifteen I thought nothing of walking into a chemist’s shop and buying a syringe if I needed it for my biology studies. At that time I was totally unaware of drug abuse of any sort other than alcohol.

[1] the copper kettle is discussed in chapter 7.

[2] A case for the retention of chloroform as an anaesthetic agent was made as late as 1981 by Prof. J.P.Payne in his interesting paper Chloroform in Clinical Anaesthesia. Brit.J. Anaesth. 53:11S. He reminded us of the favourable reassessment of chloroform by Waters in 1951 (Chloroform: a study after 100 years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press). He pointed out that in many parts of the world there was a need for a safe volatile agent which was also cheap, potent, non-explosive and easily transported and stored. He wrote that

... those who are familiar with the drug will argue that chloroform meets these criteria, particularly if it is used in the modern fashion using thiopentone to induce anaesthesia, an established airway and oxygen as a carrier gas. ...many will find chloroform used as described a good compromise.

[1] After the death of John Snow in 1858, Joseph Clover (1825 -1882), a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, became the leading clinical and investigative anaesthetist in Britain. He was Lecturer in Anaesthetics at UCH, Chloroformist to the Westminster Hospital and Administrator of Anaesthetics to the London Dental Hospital. In 1862 he designed a chloroform inhaler which consisted of a large bag slung over the shoulder which was filled with air by means of a concertina bellows and to which a measured volume of liquid chloroform was added.

For further details see Macintosh RR, Mushin WW. Physics for the Anaesthetist. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd. 1946. He also designed invented a ‘portable regulating ether inhaler’ - Brit. Med J. 1877; i, 69 - which was very successful and helped re-establish ether as the safest and most efficient anaesthetic for routine use. For a review of this apparatus one hundred years later, see Atkinson RA, Lee JA. Anaesthesia 1977; 32: 1033.

[2] Published in 1947 by Sigma Books Ltd, London. Curiously enough, I see that in the Acknowledgements it says:

The author has been helped in his anesthesia studies by the descendants of Samuel Guthrie, the discoverer of chloroform, particularly by his grandson, Thaddeus Samuel Chamberlain.

email john@johnpowell.net