Extract from A History of the Bristol Royal Infirmary by G. Munro Smith. Bristol: Arrowsmith, 1917

William Hetling was born in 1773. His father, whose name was also William, lived in Bath, where (according to Mr HE Hetling) “he pursued his adventurous and ruinous career of Surgeon, Distiller of Spirits, absconder to Gretna Green with an heiress for his wife, finishing up with the seizure of the distillery by the Excise and the company of Light Infantry, a bankruptcy, a flight to Paris, and most probably a bloody end during the orgies of the revolution, for when that was over Mr William Hetling appeared to be over two, for nothing more was heard of him.”

The heiress above referred to was a Miss Rishton, whose guardian naturally intended her “for his son Tom.” “She fell in love,” says Richard Smith, “with Mr H, who was a dashing handsome man. They agreed that she should wait at famous pye-shop in Broad Street; and here, having joined him, he popped her into a post-chaise and rattled off to Gretna Green!”

The Hetlings were of German extraction, and came to England in the train of the Georges from Hanover.

William Hetling, the subject of this biography, was indentured to Joseph Metford as an indoor apprentice, for which his father paid 300 guineas. He went to Guy’s and St Thomas’s and settled first at Chipping Sodbury. In December 1794 he married Miss Ann Brown, daughter of Mr Brown, iron monger, of Bridge Street Bristol. He came to this city about the year 1806, and resided at Colston Parade, he unsuccessfully applied for the vacancy as Surgeon to the Royal infirmary on the death of the senior surgeon, Mr Geoffrey Lowe, but was elected the following year on June 2, 1807 in the vacancy caused by the death of Mr FC Bowles.One of the disadvantages of the old method of canvassing for infirmary posts was this, that the mere suspicion of resignation at once brought candidates into the field, and votes were so often given to the first person to ask for them, that priority was everything. Consequently, when a Physician or Surgeon on the Staff became seriously ill, the temptation to begin a secret canvass sometimes induced applicants to start before the breath was out of his body. This happened when Godfrey Lowe was in his last illness, and several days before Bowles’s death, the trustees were asked to “reserve their votes!”

A few months after Hetling’s appointment there occurred one of the numerous difficulties about apprentices.

A young man named Adams had been admitted under the Surgeons as a pupil for one year, stating that he had already served four years apprenticeship in Wales. It was found that this was incorrect, and that he had served for two years only. The rule was that every apprentice was served for five years and least, and could only be entered at the Infirmary for the whole of that period or for its completion. He was therefore requested to pay the additional premium required. This he failed to do, and the Surgeons decided that his money should be refunded, and that he should not be admitted to the House.

The premiums paid by pupils were divided equally among the Surgeons, and all but Hetling refunded their shares to Adams.

A few days after this Richard Smith was about to operate on a stone case, when Hetling entered the room and said, “as a matter of right I introduce Mr Adams as my apprentice.”

This was considered such an affront that “an altercation ensued“, and Richard Smith, although a man of great nerve, and by no means easily upset, “judged it desirable to postpone the operation“, feeling that it was not wise to undertake the delicate manipulation in an agitated condition

This controversy was finally referred to Mr Edmund Griffiths for a legal opinion. He decided according to the rules of the Infirmary Adams should not have been introduced to the Operation Room.

This dispute, although it appears trifling to us, was of importance, because it was one of the many which caused division among the the Surgeons, and helped to bring about the exclusion of the Faculty from the Committee.

Hetling’s activities at the Infirmary as a lecturer are mentioned in other parts of this volume.

He resigned in November 8, 1837, after more than 30 years service, and died on November 11 of that year at his house in Royal York Crescent, Clifton, aged 64 years.

An account of his last days, and his pathetic farewell to the Institution it was so attached to, will be found on page 306.

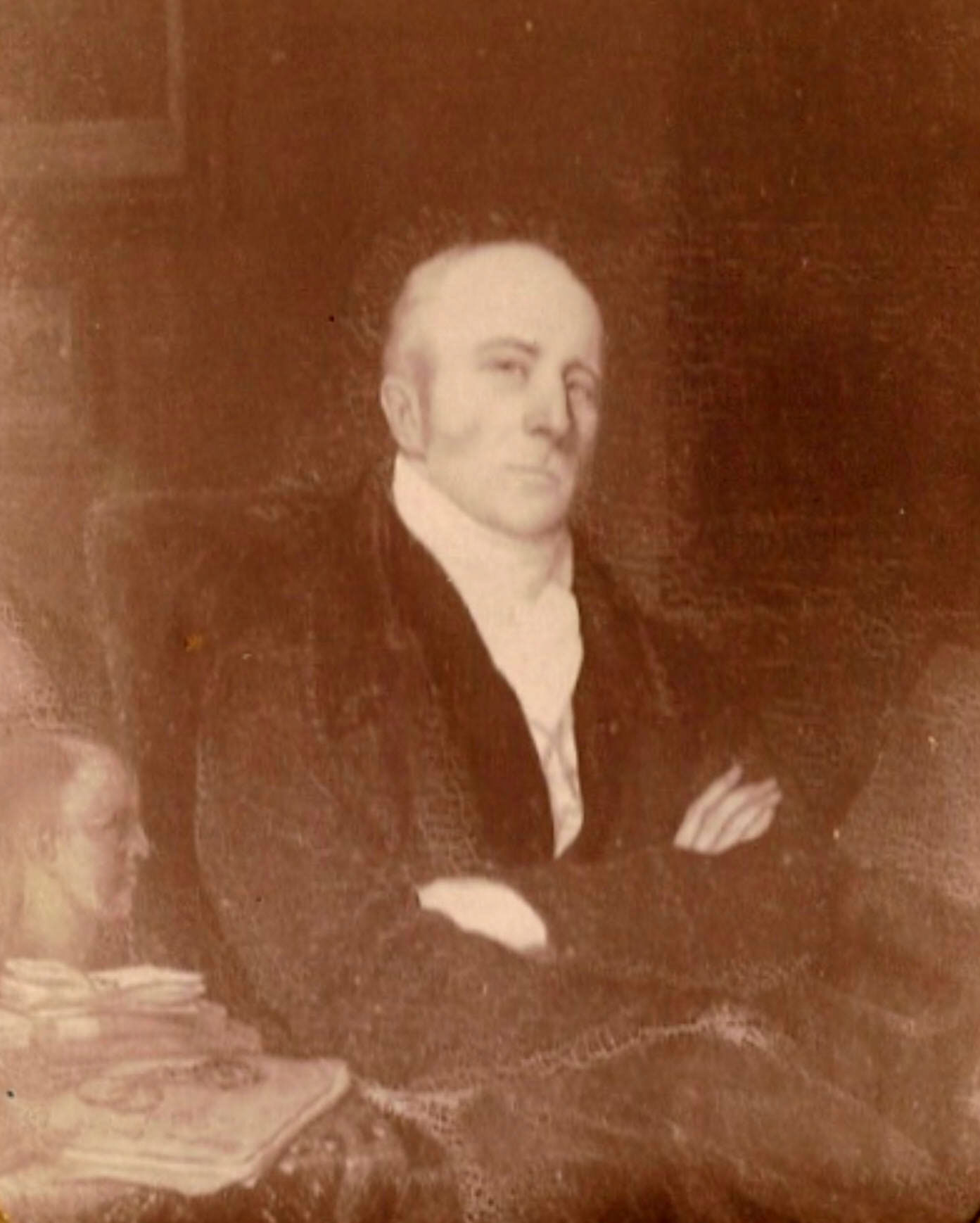

It will be gathered from various references to William Hetling in this history that he was a man of great determination and rather prone to quarrel. Mr HE Hetling used, as a child to spend much of his time at his grandfather’s estate at Shiplake and writes to me: “Everybody in the house sooner or later had to change in battle with the old gentleman … part he was a man of strong and determined character, a great mental capacity, and have considerable reputation. He was established in practice before the College of Surgeons was chartered and he received from them a request to accept their diploma.”

Mr Henry Alford writes:

“Mr Hetling was a slight, thin man, not very free or communicative with his pupils; regular in his visits to the Infirmary, and he took a great deal of pains with his patients there. He drove a close carriage and pair in his professional visits, but he is sometimes walked to the Infirmary.”

NB in the index of Munro Smith’s A History of the Bristol Royal Infirmary there are 29 pages, scattered throughout the book, dealing with William Hetling. The extract above is taken from just 3 of them.