Clevedon Ventilator

Contents

II. Poliomyelitis - general discussion and incidence in Bristol.

III. Treatment of life-threatening poliomyelitis, including use of the Clevedon Ventilator.

IV. Technical description of the Clevedon ventilator

NB click any picture to enlarge it

The Clevedon ventilator was designed by Dr James Macrae and his colleagues at Ham Green Hospital in 1953 to treat life-threatening poliomyelitis. It was built by Willcocks Engineering Co., Clevedon. One remaining ventilator is housed in the Monica Britton Memorial Hall for the History of Medicine at Frenchay Hospital , Bristol. This webpage is based largely on the pamphlet I prepared to go with the ventilator to the museum.

Photo of the Clevedon Ventilator taken November1993.

Dr James Macrae

Resident Physician, Ham Green Hospital 1947-76

with a young patient (note tracheostomy)

The first patient it was used on was Max, aged twenty one.

Here is Max in 1993, 40 years later.

Poliomyelitis is the only common disease in which sudden paralysis can occur in a previously healthy infant or young child. (Paul JR. 1971). It is an acute illness that follows invasion of the gastro-intestinal tract by one of three types of poliovirus. The infection may be: - clinically inapparent, a minor febrile illness, an aseptic meningitis, or an illness with paralysis (<2%)

Symptoms include headache, gastrointestinal disturbance, malaise and stiffness of the neck and back, with or without paralysis.

The word 'poliomyelitis' comes from the Greek polios, grey, and myelos, marrow. It is probably a disease of great antiquity.

Egyptian stele, dating from the eighteenth dynasty (1580-1350 BC), now in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. (Photograph by courtesy of the Glyptotek.)

Note the withered and shortened leg, with the foot held in the typical equinus position characteristic of flaccid paralysis. Poliomyelitis is the most likely cause. (Hamburger O. 1911)

The earliest case on record in the British Isles is Sir Walter Scott (b. 1771)

I showed every sign of health and strength until I was about 18 months old. One night, I have been often told, I showed great reluctance to be caught and put to bed, and after being chased about the room, was apprehended and consigned to my dormitory with some difficulty. It was the last time I was to show much personal agility. In the morning I was discovered to be affected with the fever which often accompanies the cutting of large teeth. It held me for three days. On the fourth, when they went to bathe me as usual, they discovered that I had lost the power of my right leg.

... when the efforts of regular physicians had been exhausted, without the slightest success...

the impatience of a child soon inclined me to struggle with my infirmity, and I began by degrees to stand, walk, and to run. Although the limb affected was much shrunk and contracted, my general health, which was of more importance, was much strengthened by being frequently in the open air, and, in a word, I who in a city had probably been condemned to helpless and hopeless decrepitude, was now a healthy, high-spirited, and, my lameness apart, a sturdy child. (Lockhardt's Memoirs of Sir Walter Scott, 1837)

The disease was not described in the medical literature until 1789:

Debility of the Lower Extremities.The disorder intended here is not noticed by any medical writer within the compass of my reading, or is not a common disorder, I believe, and it seems to occur seldomer in London than in some parts. Nor am I enough acquainted with it to be fully satisfied, either, in regard to the true cause or seat of the disease, either by my own observation, or that of others; and I myself have never had the oportunity of examining the body of any child who has died of the complaint. I shall, therefore, only describe its symptoms, and mention the several means attempted for its cure, on order to induce other practitioners to pay attention to it.

It seems to arise from debility, and usually attacks chidren previously reduced by fever; seldom those under one, or more than four or five years old.

(Underwood M. A Treatise on the Diseases of Children with General Directions for the Management of Infants from Birth. 2nd edition. Mathews, London 1789)

And from the 4th edition (1799) -

The Palsy ... sometimes seizes the upper, and sometimes the lower extremities; in some instances, it takes away the entire use of the limb, and in others, only weakens them.

Its epidemic nature was not recognised until 1891. (Karl Oscar Medin, Stockholm). From then on, the disease ceased to be a curiosity and became in some countries a periodic scourge.

The poliovirus was discovered in 1908. (Karl Landsteiner, Vienna). Poliomyelitis became a notifiable disease in the UK in 1912, following three small outbreaks in the South West of England in 1911. During the first forty years of this century, there were periodic epidemics in North America, Scandinavia and in other parts of the world. The change from endemic polio to epidemic polio was probably the result of improved hygiene in the latter part of the 19th century. This allowed an increasing number of children to avoid primary exposure during infancy, when they would still have had passive immunity from their mothers. Exposure at this stage, which was normal in populations living in unsanitary conditions, almost invariably led to lifelong natural immunity. Nevertheless ...

Acute poliomyelitis has not yet occurred in Great Britain as a major epidemic. However, there have been several grave outbreaks in countries where the meteorological and environmental conditions are not sufficiently different to our own to inspire any confidence in a continuation of our comparative immunity. (Picken R. 1940)

In 1945-46 many servicemen returned to the UK from the Far East where polio was very prevalent.

Despite this the incidence of polio in Britain in 1946 was lower than that in 1938. But during the warm dry summer and autumn of 1947 the prevalence of acute anterior poliomyelitis increased in Britain to an extent never before recorded. (Macrae J. 1950)

In BRISTOL the incidence lagged behind that of the country as a whole (see opposite), but in 1950 there were 316 cases of poliomyelitis, with 32 deaths; the rate per 100,000 population (60.2) was three times the national average. Of these 316 patients 53 reqired treatment in a ventialtor and the mortality was 50%.

The second highest number of cases of confirmed poliomyelitis in Bristol in a single year was in 1955; there were 158 cases with the following geographical distribution:

|

Southmead |

68 |

|

Lawrence Weston |

18 |

|

Knowle & Knowle West |

15 |

|

Bedminster |

10 |

|

Horfield & Lockleaze |

9 |

|

Avonmouth & Shirehampton |

7 |

|

Brentry and Henbury |

6 |

|

Clifton |

5 |

|

Easton & St George |

5 |

|

Redland & St Pauls |

5 |

|

Fishponds & Stapleton |

3 |

|

Henleaze |

2 |

|

Kingswood |

2 |

|

St Anne's |

2 |

|

Hartcliffe |

1 |

In 1957 there was another peak in Bristol of 98 cases. This time there was only one case from Southmead; it is likely that widespread clinically inapparent infection in 1955 had produced widespread natural immunity in the Southmead population.

From then on the incidence of the disease fell due to the introduction of the Salk (killed virus) vaccine in 1956 and the Sabin (live attenuated virus) vaccine in 1962.

The effect of vaccination in various parts of the world:

|

Average annual no. of cases |

in 1951-55 |

in 1961-65 |

|

|

|

|

|

United States |

37,864 |

570 |

|

Australia |

2,187 |

154 |

|

New Zealand |

405 |

44 |

|

Austria |

607 |

70 |

|

Belgium |

475 |

79 |

|

Czechoslovakia |

1,081 |

6 |

|

Denmark |

1,614 |

77 |

|

Sweden |

1,526 |

28 |

|

United Kingdom |

4,381 |

322 |

(figures from WHO 1968 quoted by Paul JR 1971)

The World Health Organisation forecasted that poliomyelitis would be eradicated by the turn of the last century. They almost made it! The latest forecast is for 2005.

III. TREATMENT OF LIFE-THREATENING POLIOMYELITIS

In 1929 Dr Phillip Drinker, of the Harvard School of Public Health, designed his "tank respirator", or the "Iron Lung" as it was popularly called. This consisted of a rigid cylinder into which a patient could be placed, and within which negative pressures could be applied at regular short intervals.

In 1938 William Morris, later Lord Nuffield, gave tank respirators to any British hospital that asked for them.

In 1949 Bower and his colleagues in Los Angeles reported great success during the 1948 epidemic with intermittent positive pressure respiration (IPPR) applied to the airway. They had two Bennett positive pressure valves which they used:

However they did not foresee that intermittent positive pressure respiration might actually replace tank respirators altogether.

It was not until 1952, when there was a massive epidemic of poliomyelitis in COPENHAGEN (population 1,200,000) that this great advance was made. From the beginning of August till the end of the year there were 3000 cases admitted to the Blegdam Hospital; 2241 of these were confirmed as poliomyelitis; 1250 had some paralysis; 345 of these needed special treatment for respiratory insufficiency and/or impairment of swallowing.

It is doubtful indeed if any city of the size of Copenhagen has ever experienced an outbreak of similar magnitude ... for many weeks we received thirty to fifty patients daily, of whom six to twelve were desperately ill ... drowning in their own secretions. As we felt that the application of modern principles of anaesthesia to the problem of obstructed airways and respiratory insufficiency in poliomyelitis might improve our results anaesthetists were invited to join our staff, the first being Dr. Bjørn Ibsen. (Lassen 1954a)

Dr Ibsen was called into consultation on August 25th. In the preceding three weeks there had been 31 patients with life threatening poliomyelitis; 28 of these had died. On August 27th the first patient was treated with the method that was to become the treatment of choice:

The apparatus used for ventilating these patients was amazingly simple:

At times there were as many as 70 patients requiring artificial respiration. Students from the University provided the manpower (handpower!). Overall 1400 students were involved during the course of the epidemic. None of them contracted the disease.

By the end of the year the mortality in these severe cases had fallen from 87% to 26%.

A sketch of Bjørn Ibsen from "From Anaesthesia to Anaesthesiology. Personal experiences in Copenhagen during the past 25 years." Acta Anaes. Scand. supplementum 61. 1975.

Despite the striking success of tracheotomy combined with intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPR) in Copenhagen in 1952, tank respirators remained in use in the USA until 1960. However, in Denmark in 1953 Bang designed an automatic respirator, and subsequently in the UK several new automatic ventilators were described the same year (Beaver, Radcliffe, Clevedon and Pask Mks 1-5). The Clevedon ventilator, a minute volume divider similar to the Bang ventilator , was designed at Ham Green Hospital:

With the financial approval of the South West Regional Hospital Board, and the expert assistance of Mr MJ Willcocks, of Willcocks (Clevedon) Ltd, Instruments Section, a prototype was produced. Improved patterns were available by the middle of July. (Macrae J 1950)

(At one time in his career Mr Willcocks was mechanic to Sir Henry Segrave during attempts on the world water speed record. The firm of Willcocks is still in business.)

The new ventilator was used on a patient (Max) for the first time on Sept 28th 1953:

A well-developed man, aged 21, was admitted at 6.30 am on Sept. 28th, 1953, with severe poliomyelitis. At 7.30 am he was placed in a Drinker-type tank respirator because of partial failure of his respiratory muscles. During the day his paralysis spread, and by 6 pm the respiratory muscle paralysis was almost complete. In addition he had developed bulbar involvement, with inabiltiy to swallow, and was accumulating pharyngeal mucus. Continued treatment in the tank respirator was obviously going to prove rapidly fatal, since it was impossible to keep the airway clear. It was decided to try the positive-pressure ventilator. (Macrae J. 1948)

Max was on the Clevedon ventilator for six weeks from 28th September. He was finally discharged in May 1954, having made an excellent recovery. By this time his Vital Capacity had recovered to 1800ml.

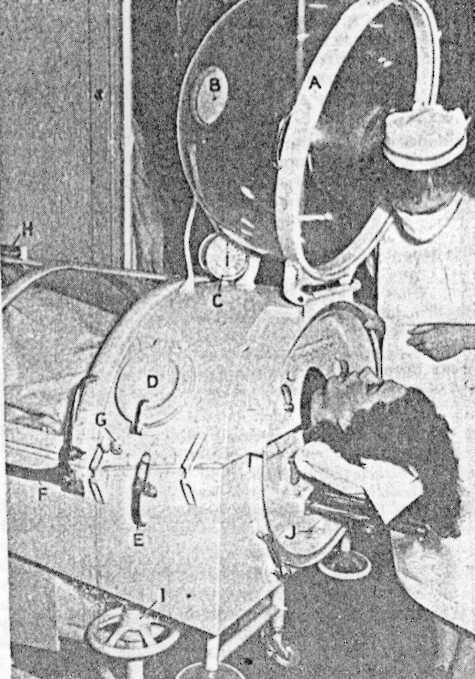

First use of the Clevedon ventilator, September 1953

The electrolytic switches seen here were changed to tilting mercury switches in later versions.

That same year, 1953, Macrae and his colleagues also introduced a new tank respirator that incorporated a head dome. This dome could be closed when the tank itself was opened, so that intermittent positive pressure could be applied to the patient's airways, allowing nursing procedures to be unhurried compared to the old type of tank ventilator (Macrae et al 1954b).

The Bristol tank respirator with head dome, from Macrae et al 1954b

It was not until 1957 that two wards (I & J) at Ham Green Hospital were set aside as special accommodation for the treatment of life-threatening poliomyelitis.

For 12 years after 1947 we treated about 1500 cases of acute anterior poliomyelitis demonstrating various degrees of paralysis. This was an evocative disease in every sense and, apart from public concern, these patients required maximum medical and nursing care. If the old fever hospital developed anything it did evolve an exceedingly high level of personal bedside nursing in a ward environment affording plenty of room between beds. This nursing background and and the demands of a dreaded disease continued to allow us to give these patients the very best of nursing care. Such a high proportion of patients needed artificial respriation that a new and complex discipline was added to both medical and nursing management.

Initially these patients were treated in isolation wards which catered for many patients with other diseases. Even before the advent of positive pressure respiration in 1953, it was becoming painfully obvious that severe cases of poliolmyelitis required separate accomodation. But it was not until the 15th of August 1957 that a ward with special rooms and facilities was taken into use. Without knowing it, we had evolved an intensive care unit and the transformation was extraordinary. This was especially evident among the nurses who were able to concentrate on their duties to individual patients each with individual problems. Quite suddenly the whole business of artificial repiration took on a calmness never experienced in a mixed ward. (Macrae J. 1969.)

There were about thirty Clevedon ventilators built in all, several of which were sold in Ireland.

Although a Clevedon has not been used for many years now at either Southmead or Ham Green Hospitals, one was in constant use until 1992 by Dr Ted Nesling in the anaesthetic room of the neurosurgical theatre at Plymouth.

Following his discharge from Ham Green in 1954, Max remained well, apart from mild hypertension, until 1979 when he was admitted to the ITU at Southmead Hospital with respiratory problems due to retention of secretions resulting from weakness of his cough. By 1981, after three further admissions, twice to Southmead and once to Frenchay, it was clear that, in addition to his weak cough, he was seriously underbreathing when he was asleep. He was finally discharged home from Southmead in May 1981 with a permanent tracheostomy (silver tube, uncuffed) and with his own ventilator (initially an East-Radcliffe; later a Cape Minor).

During the day he would block off the silver tube and would wear a collar and tie. At night he connected himself to the Cape. Max got on extremely well for more than twelve years. When he travelled he took his Cape with him. The photos below were taken in September 1993, 40 years after his original admission to Ham Green Hospital.

Max and his much travelled Cape minor

Sadly Max died in 1998.

IV. TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE CLEVDON VENTILATOR

diagram of the Clevedon ventilator from Mushin et al (1965)

1. Solenoid 2. Solenoid operated inspiratory -expiratory valve 3. Expiratory tube 4. Inflating gas inlet 5. Solenoid 6. Closed chamber 7.Tilting mercury switch 8. Rack and pinion 9. Reservoir bag 10. Rack and pinion 11.Tilting mercury switch 12 Push rod 13. 12 -volt battery/transformer 14. Left-hand limb of U-tube 15. Float 16. Adjustable one-way valve controlling duration of expiratory phase 17. Right-hand limb of U-tube 18. Float 19. Adjustable one-way valve controlling duration of inspiratory phase

The Clevedon is a minute volume divider, dependent upon a solenoid-operated inspiratory-expiratory valve. During the expiratory phase compressed air enters the machine and distends the reservoir bag. Change-over from expiratory phase to inspiratory phase is time-cycled, when switch 7 is operated by enough water having leaked through control tap 16 at a rate, and therefore in a time, which is determined by the tap setting. During the inspiratory phase the bag operates either as a discharging compliance or a constant-pressure generator depending on how distended it is. Change over from inspiratory phase to expiratory phase occurs when the pressure in the chamber has driven enough water through control tap 19 to operate switch 11. During the expiratory phase the partient's expired gases pass freely to atmosphere.

For a fuller account see Mushin et al (1965).

Bower AG and Associates (1950) A Concept of Poliomyelitis Based on Observations and Treatment of 6000 Cases in a Four-Year Period. Northwest Medicine 49: 261-266.

Hamburger O (1911) A case of infantile paralysis in ancient times. Ugeskr. f. laeger., 73:1565.

Lockhardt JG (1837) Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart, vol. 1, Carey, Lean and Blanchard, Philadelphia.

Medin KO (1891) Ueber eine Epidemie von spinaler Kinkerlahmung. Verh.X Internat.med.Kongr., 1890. 2:Abt.6

Lansteiner K and Popper E (1908) Mikroscopiche Praparate von einem menschlichen und zwei Affrückenmarken. Wein. klin. Wschr., 21.

Lassen HCA (1954a) The Epidemic of Poliomyelitis in Copenhagen, 1952. Proc Roy. Soc. Med 47:67

Lassen HCA (1954b) Management of Life-threatening Poliomyelitis. E & S Livinstone, Edinburgh & London

Macrae J (1947) Poliomyelitis in Bristol, 1947. Brist. Med-Chi J. LXIV.

Macrae J (1950) Poliomyelitis in Bristol, 1949. Brist. Med-Chi J. LXVII.

Macrae J (1954) Poliomyelitis in Bristol, 1950. Brist. Med-Chi J. LX

Macrae J, McKendrick GDW, Claremont JM, Sefton EM and Walley RV (1953) The Clevedon Respirator. Lancet ii, 971.

Macrae J, McKendrick GDW, Sefton EM and Walley RV. (1954) Positive-Pressure Respiration - Management of patients treated with Clevedon Respirator. Lancet i, 21.

Macrae J (1969) A Memorandum on Infection - circulated locally, but not formally published; a typed copy is kept in the library of the Medical School, University of Bristol (Stack R11 MAC). This is such a fascinating document, dealing not just with the development of an intensive care ward as above, but also with the changes in medical practice and administration in the first two thirds of the 20th century, that I have included a copy on this site. Incidentally, it tells an interesting story of providing anaesthesia in the 1950s for routine T's and A's, and the bleeding tonsil.

Mushin WW, Rendell-Baker L, Thompson PW and Mapleson WW (1965) Automatic Ventilation of the Lungs. 2nd edition. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford & Edinburgh.

Paul JR (1971) A History of Poliomyelitis. Yale University Press: New Haven and London.

Picken R (1940) Poliomyelitis in epidemic form. Medical Annual. John Wright & Sons, Bristol

Underwood MA (1789 & 1799) A Treatise on the Diseases of Children with General Directions for the Management of Infants from Birth. 2nd & 4th eds, Mathews, London.

see also GASMAN chapter 9 - 1993 for how the pamphlet came to be written.

Home / Macrae J (1969) A Memorandum on Infection

e-mail: john@johnpowell.net

18/04/03

NB An excellent history of the Ham Green locality, and its hospital, has been written by Gerald S Hart. It is titled HAM GREEN and is published by Crockerne Books, 95 Westward Drive, Pill, North Somerset (IBSN 0 9516074 0 5).